Some cool graphite machining China images:

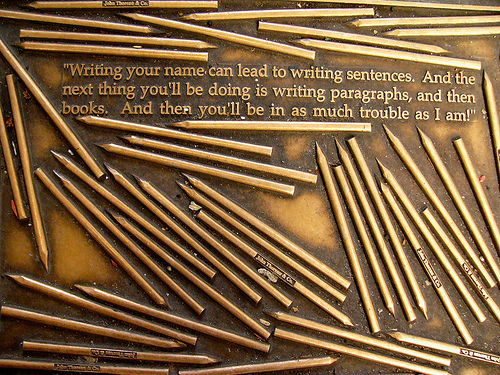

Henry David Thoreau quote – Library Way – NY City

Image by Kathleen Tyler Conklin

Henry David Thoreau (12 July 1817 – 6 May 1862; born David Henry Thoreau)[1] was an American author, naturalist, transcendentalist, tax resister, development critic, philosopher, and abolitionist who is best known for Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay, Civil Disobedience, an argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral opposition to an unjust state.

Thoreau’s books, articles, essays, journals, and poetry total over 20 volumes. Among his lasting contributions were his writings on natural history and philosophy, where he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology and environmental history, two sources of modern day environmentalism.

He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending the abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance influenced the political thoughts and actions of such later figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mohandas K. Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thoreau is sometimes cited as an individualist anarchist[2][3] as well as an inspiration to anarchists. Though Civil Disobedience calls for improving rather than abolishing government — “I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government”[4] — the direction of this improvement aims at anarchism: “‘That government is best which governs not at all;’ and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have.”[4]

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_David_Thoreau

No. 339:

THOREAU’S PENCILS

by John H. Lienhard

Today, we meet another side of Henry David Thoreau.

In 1821, Charles Dunbar discovered graphite in New Hampshire. In those days they called graphite "plumbago." Dunbar set up a pencil factory with his brother-in-law, John Thoreau. When that plumbago ran out, they went to Massachusetts and then Canada. They made a good start, considering the poverty of American graphite. Most of it had a greasy, smeary, quality. English graphite was the best available, but it cost an arm and a leg.

John Thoreau’s son, Henry David, was raised in the business. He studied at Harvard through the mid-1830’s, but he also kept a hand in the business. Pencil leads were made by filling a groove in a piece of wood with a mixture of ground graphite and some kind of binder. Henry David Thoreau worked on the problem of making a better pencil out of inferior graphite.

He solved the problem by using clay as the binder. With clay he created a superior, smear-free pencil whose hardness was controllable. He made the Thoreau company China into America’s leading pencil maker.

That catches us off guard. Was the great transcendentalist, who rose above himself on the shores of Walden Pond, a successful inventor? Was this the same man who formulated the idea of civil disobedience? Was this the person who so effectively armed Gandhi and Martin Luther King?

Thoreau’s clay-mixed graphite wasn’t entirely original. The Germans had used something like it a few years earlier. It’s not clear whether Thoreau had any inkling of the German process. But what is clear is that he transcended it. He developed a new grinding China mill. He developed all sorts of process details. Historian Henry Petroski adds to the list of Thoreau’s inventions — a pipe forming machine, water wheel designs. They probably never told you in your English class that Thoreau often signed the words "Civil Engineer" after his name.

Yet Thoreau was content to walk away from an invention without making personal profit of it. He was, after all, the same man who wrote

… the seventh day should be man’s day of toil … and the other six his Sabbath of the affections and the soul — in which to range this widespread garden, and drink in the soft influences and sublime revelations of Nature …

Henry David Thoreau is sometimes painted as ineffective in the real world. He certainly did separate himself from the mad ambitions of mid-nineteenth century America.

But his legacy to us was shaped by an engineer’s intimacy with firm-rooted reality. He knew the shores of Walden Pond were solid earth, as much as they were a flight of the mind.

——————————————————————————–

Petroski, H., H.D. Thoreau, Engineer. American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 8-16.

For more on Thoreau, see: www.library.ucsb.edu/thoreau