Check out these discharge machining China images:

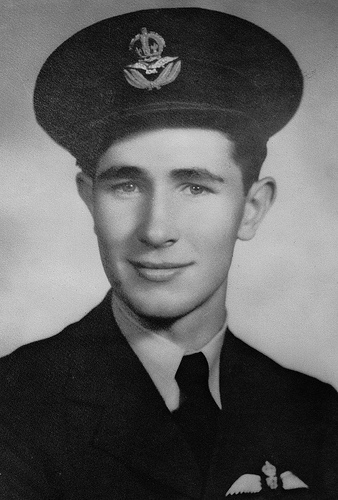

Evan Campbell (Cam) Devine, Uncle Bill Watson’s Friend

Image by bill barber

From my set entitled "Uncle Bill Watson"

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/sets/72157600269993237/

In my photostream

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/

Watson reunion photo in which Cam Devine appears

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/536290657/in/set-72157…

Campbell (Cam) Devine was my Uncle Bill Watson’s best friend during early school years in Grand Valley, Ontario. Cam was killed on August 12, 1944, when the Flying Boat he was piloting crashed in Ireland. I am including a notice of his death from the Grand Valley Star and Vidette, and a detailed account of the crash as remembered by Chuck Singer, one of Cam’s flight crew.

From The Grand Valley Star and Vidette, August, 1944

Another Grand Valley Boy Passes Overseas

News of the death of another Grand Valley boy overseas was received in town the latter part of last week. He was Flight Lieut Campbell Devine, elder son of Dr. and Mrs. E. W. Devine of Orillia formerly of Grand Valley. Campbell was born in Grand Valley and moved with his parents to Orillia some years ago. His death occurred in Ireland on Aug.12 and interment took place in Ireland. He was a chum and pal of the late P.O. Bill Watson of Grand Valley. Brief references to his death were made in the pulpits of Knox Presbyterian Church on Sunday morning and at the memorial service for the late P.O. Watson in Trinity United Church on Sunday afternoon. Besides his parents and one brother, Donald, the deceased leaves a widow and one child, all of Orillia. To the bereaved parents, brother, widow and child the sympathy of this community is extended

Full particulars regarding his death had not been received at the time of going to press.

Taken from THE BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC Highlights from 422 R.C.A.F. Squadron, 1942 – 1945

www.airforcemuseum.ca/422ww2.htm

August 12, 1944 saw the crash of Sunderland T of 422, in Donegal County, Ireland, just north of Belleek, Northern Ireland, shortly after take-off for an Atlantic patrol. The heavily loaded aircraft had suffered an engine fire and loss of propeller and a crash landing was attempted on a relatively flat area. The skipper, F/L Cam Devine and two crew members died in the crash. The remainder of the crew received serious injuries and were initially treated in the Irish hospital in Ballyshannon, Donegal County, and later moved to the military hospital in Necarne Castle near Irvinestown, Northern Ireland or to hospitals in England.

Taken from the The Impartial Reporter: For Fermanagh, Tyrone and Border Counties of the Republic of Ireland:

Issue: 15-08-2002

www.impartialreporter.com/archive/2002-08-15/news/story41…

A tear ran down the cheek of Chuck Singer as he stood on the windswept bogland of Cashelard, receiving long overdue recognition for an act of great courage undertaken 58 years ago to the day.

It was a marvellous moment, a fitting closure to a remarkable tale, owing much not only to Chuck, whose selfless actions as a 19 year old First Gunner on a stricken Sunderland flying boat in 1944 saved the life of a comrade, but also to his son Bob (who correctly pointed out that reports of his father’s death in the Squadron records were greatly exaggerated), and local historians Joe O’Loughlin and Breege McCusker.

A large crowd gathered on Monday at the exact hour at the site where Sunderland NJ175 crashed shortly after taking off from its base at Castle Archdale. They gathered to pay tribute to Sergeant Chuck Singer, but also to the three airmen who did not survive the crash, and whose names are recorded on a memorial stone erected at the site two years ago. With a beautiful ceremony choreographed brilliantly by Joe and Breege, interspersed with presentations to Chuck, the crowd listened to a recounting of the Canadian’s remarkable story.

422 Squadron Royal Canadian Air Force arrived in Fermanagh in the spring of 1944, youthful, joyful crews of men who had thus far generally enjoyed their war experiences, stationed with Coastal Command in Scotland, protecting Merchant Navy convoys from the threat of German U Boats.

They were to do the same job from their base on Lough Erne, patrolling out into the Atlantic and also into the Bay Of Biscay and the English Channel. Their role was an important one- the U Boats were the only cog of the German war machine which really frightened Churchill, and any break in the Allies supply line would have had a debilitating effect on the war effort.

But to the airmen based in quiet County Fermanagh, on the usually serene Lower Lough Erne, the war must often have seemed a world away. Chuck remembers that conditions on the base were "beautiful, just fine", and that even when they were airborne, patrolling at an average altitude of 400 feet, there was never any real feeling of unease or fear.

"We felt like nothing was ever going to happen to us out there. To fly was just a treat to get up and if they ever postponed a flight on us we got sick, you know, just sick. I don’t know any aircrew that ever worried- it was all jovial, funny guys that had a good time, I don’t know anybody that ever worried about dying. Flying out to sea in those things was so peaceful. You almost forgot that you had a job to do it was so beautiful and peaceful."

During his short spell in Fermanagh, Chuck fortunately never had to fire his guns in anger from his position in the turret at the top of the giant seaplane, but remembers one occasion when his crew felt they were about to have their first serious engagement with the enemy.

"We thought we had a pair of them one time," he said. "It looked like a mother ship refuelling a smaller sub, so we dived at that thing, we had all the depth charges out on the wings, we were ready for everything… and they were two of the most beautiful Blue Whales you ever saw in your life."

Chuck left his turret and aimed a camera instead of his machine gun. He took a couple of photographs and left them in to get developed back at the base, but due to his unfortunate exit from Castle Archdale he was never able to pick them up again. "We went out feet first and I never did get them. I’d loved to have had those pictures," he said wistfully.

The biggest threat to their safety that Chuck encountered during the patrols actually came from the Merchant Navy which the Sunderlands and Catalinas were sent to protect. Engagements with enemy aircraft and U Boats were rare by 1944, but the Merchant convoys were jumpy, and fairly ‘trigger happy’ recalled Chuck.

"The worst part was flying alongside a convoy, because those merchant people- they were shooting at everything, and they didn’t know us from the enemy. When we used to approach a convoy the skipper used to give them every view they could of the markings or else the Merchant Navy would shoot you down."

They would also shoot coloured flares by way of identifying themselves, but the colours were changed frequently, and sending up the wrong colour could prove fatal. Call signs were also used for identification and changed frequently, but there is one call sign which is indelibly printed on Chuck’s memory. ‘Eyeglass Eagle’. This was the last call sign of Sunderland NJ175, as it took off around 11:15 on Saturday morning, August 12, 1944. NJ175 was like any other Sunderland docked at the Flying Boat base, and was supposed to have been checked by the engineers before take off. Every one of the 12 man crew had checks to make after being rowed out to the boat on a dinghy.

"When it was our turn to fly they’d put us in a dinghy from the dock and run us to one of the boats, and we’d get on it and check everything out, and if something wasn’t right we’d radio the dinghy and it would come back and get us and take us to another one. Often there’d be two or three before we’d get one that was operational."

Everything happened in such a hurry that it was fairly common to experience mechanical problems, said Chuck, and often the crews would be delayed at least an hour by repairs.

On the flight on August 12 was his regular crew, all of whom had got to know each other like brothers, having flown and socialised together in Fermanagh for months, as well as a few trainees, learning the ropes, and sitting, fatally as it turned out, near the cockpit behind the skipper, Flight Lieutenant Cam Devine.

They were heading for the English Channel, hoping to catch the German subs heading for Norway from their base at Brest on the French coast. The men- all members of the RCAF, were expecting to be away for between 10 and 12 hours, burning an enormous 2000 gallons of fuel. As it happened, they were only airborne for a fraction of that time- about 30 minutes- and had to dump as much of the fuel as possible over the surrounding area.

"The engine sounded uneasy all the time after we took off. It just didn’t sound like it was hitting all cylinders, it sounded funny. But sometimes that clears up, but this time it didn’t," said Chuck. The noises got worse as the plane reached the West Coast of Ireland and a problem in the outer starboard engine had developed into a fire. The crew sent out a mayday call and turned around to return to base. Orders came in from Castle Archdale to jettison the fuel and the depth charges on board, which would have exploded on impacting with the ground.

Local people in the fields around Belleek were used to seeing the huge Flying Boats sailing out to war over their heads along the secretly negotiated Donegal Corridor, but to see one with thick black smoke billowing out from its starboard engine was an unusual and alarming experience. Although Cashelard is a remote area, there were a number of people in the vicinity, taking advantage of the great weather to work in the fields or enjoy the first day of the Grouse shooting season. Their peace was about to be shattered.

On board the plane, dumping the 2000 gallons of fuel was proving too dangerous, as the high octane fuel was pouring out perilously close to the burning engine, risking an explosion which would blow the plane to smithereens. Flying Officer Alex Platsko, the Second Pilot, whose job it was to jettison the fuel and depth charges in preparation for a less than routine landing, now had to shut off the fuel dump valve again.

And there was another problem- the track for the depth charges was sticking, and the crew couldn’t get them out of the plane. Eventually, after a desperate struggle, the crew worked the charges free, and they dropped harmlessly to the ground, to be blown up next day by the Irish Army and officials from Castle Archdale.

Platsko returned to the task of shutting off the fuel dump valve, but was shuddered out of his work by a loud bang as the burning engine suddenly froze up and the propeller twisted off its shaft and spun into the starboard float, causing the plane to bank suddenly, steeply to the right. Chuck remembers the sharp snap of the propeller breaking off, not long before impact.

Skipper Cam Devine, just 22 years of age, had a fight on his hands. With one engine on fire and out of action, and a half a tonne propeller embedded in the side of one of his floats, the plane was losing height at a frightening rate and in danger of hitting the ground sideways first. "We could’ve cartwheeled – if the wing had touched first we would all have been dead," said Chuck.

The crew members were adopting the crash position, something similar to what is advised on commercial airliners today, but without the fancy demonstration cards. Cam Devine was fighting for his life, and the lives of his comrades, fighting to get the heavy plane back on an even keel to give them a chance in the crash landing which was now inevitable. Somehow, against the odds, he achieved this, righting the plane just before impact on the Cashelard ground, succeeding in saving the lives of nine of his crew members, but losing his own life in the process.

Chuck remembers certain aspects of the impact, but he was concussed, and blood was streaming down his face. Three of the crew- Cam Devine, Pilot Officer R.T Wilkinson and Flight Sergeant Jack Forrest- died instantly. Alex Platsko, who hadn’t time to buckle himself back into his seat after jettisoning the depth charges, was thrown through the windscreen, and survived, although he was seriously injured.

The plane hit the lip of a country track, coming down perpendicular to the road rather than along it, which caused the bottom half of the plane to be severed in the sudden halt. "When the bottom half of the plane was torn out I was up in the ceiling getting my arms broke and my face cut, and concussion, and I was looking down and I could see George Colbourne laying face-up on the bottom of the boat," recalled Chuck. "We went over the top of him, but it looked like we were still and he was sliding on a toboggan underneath us- that was the effect we got. That was the last thing I remembered until I gained consciousness again and tried to get out of that thing."

The next thing he remembers is the heather all around the crash site being on fire. The Sunderland had broken in two places- at the tail, and between the under section and the rest of the plane. The tail breaking off was a blessing in disguise, affording an escape hatch for Chuck and some of the other crew members.

Dazed, bleeding, and with his left arm hanging limply by his side, Chuck somehow got out of the mangled remains of the plane. As aviation fuel leaked out of the plane the fire spread, and bullets and ammunition were exploding in the heat. Chuck staggered clear of the heat, but heard George Colbourne crying for help. George was trapped under the wreckage of the tail, powerless, with two broken legs. Chuck turned back into the flames.

"I can remember going back when I heard him crying and screaming. I heard him before this, and I thought ‘God, I’m not going to get him’, and then he screamed one more time and I thought: ‘I’ve got to get him’, so I went back after him. I pulled my arm out hauling him out- I tore a ligament in my shoulder. I couldn’t use my left arm- it was broken. So by the time I got him maybe 50 to 100 feet away, I don’t know how far it was- until I couldn’t feel the heat anymore- I passed out, and so did he."

The fire totally engulfed the plane, but somehow all of the survivors had got clear of the wreckage. Joe O’Loughlin reached the plane on his bicycle about half an hour after the crash, along with other locals and helpers, including the supposedly neutral Irish Army from Finner Camp, rescue services from Castle Archdale, and medical staff from Ballyshannon’s Shiel Hospital. All of the injured, with wounds ranging from a broken back to severe burns, were taken to the hospital, where they remained for 48 hours before being transferred to St Angelo Airport and over to hospital in England.

At this point, according to the records of 422 Squadron, Sergeant Charles (Chuck) Singer died. This was quite an alarming discovery for Bob Singer in January this year, who thought that his father had recovered from his injuries, received a medical discharge and flown back to Canada, where he later married, had five children and moved to Florida, keeping in contact with George Colbourne, who rang him every year on August 12 to thank him for saving his life on a lonely Irish bog, a lifetime ago. Bob had decided to do a little research into his father’s Airforce career, and had stumbled upon the Squadron records. He knew very little of the crash, and nothing of his modest father’s heroic rescue of Colbourne. He sent a reply to the website, stating that as his father had been helping him in the yard that morning, and notwithstanding a Lazurus-like reincarnation, he had not died in England on August 14, 1944, as the Squadron notes reported. Chuck had missed out on over 50 years of squadron reunions thanks to an erroneous report in the records. He had no idea that there was such interest in those based at Castle Archdale: "I didn’t have a clue- I thought that we were all forgotten. Joe here, he got after me right away- I got a letter within a week from him."

He also got in touch with the courageous Alex Platsko, now Dr Alex Platsko, who lives in the prestigious Pebble Beach resort in California. The two old comrades talked together for the first time in 58 years a few months ago, while Chuck ordered his Squadron badge, an honour he had neglected for over half a century.

This has been a year of amazing discovery for both Chuck and Bob, who accompanied his father on his emotional return to Fermanagh and to Cashelard. Under the gentle guidance of Joe, they have revisited so many areas of huge significance for Chuck- the well kept war graves in Irvinestown where his three comrades are buried; Castle Archdale with Breege McCusker; the Shiel Hospital in Ballyshannon where Chuck asked the staff if he owed them anything and joked that he had "an outstanding bill from ’44"; and finally, most emotionally of all, the site at Cashelard where Sunderland NJ175 crashed 58 years ago to the day.

Full of praise for the people of Fermanagh- "a wonderful race", Chuck returns this week to Florida, laden with gifts such as a mounted piece of the wreckage of his plane, a framed citation commemorating his bravery, a copy of the memorial plaque erected to the memory of his fallen comrades, and a replica model of the planes in which he soared above the seas, risking his tomorrow for our today.

Having been reaquainted with his squadron and returned to the site of his wartime experiences he admits to being overwhelmed with his time in Fermanagh. As far as Castle Archdale, Cashelard and more particularly, Flying Boats go, he has just one disappointment, and he is not the only one: "It’s a shame there isn’t one for you guys to look at, you know? They’re all on the bottom of the lake. Isn’t that crazy?"

Taken from "Commonwealth Plots in Irvinestown County Fermanagh"

www.ww2talk.com/forum/war-grave-photographs/15812-commonw…

i265.photobucket.com/albums/ii221/lisset158/DSCF3115.jpg

The injuries to the crew Killed F/lt E.C. Devine ( Pilot ) aged 22.

( Buried Irvinestown Church of Ireland ).

P/O. J R Forrest W.Op / AG.

( Buried Irvinestown Roman catholic Churchyard).

F/O. R T Wilkinson Pilot aged 22.

(Buried Irvinestown Church of Ireland).

Surviving crew members. Sgt Allen ( Navigator).

Severe head injuries , burns to hands and legs.

Sgt Jeal. ( Flt/Engineer).

Fracture to spine , extensive burns to his hands and face.

Sgt Colbourne (A/G).

Head injury , fractured right leg.

Sgt Platsko. ( 2nd Pilot).

Head injury.

Sgt Oderskirk.(W.Op/ AG).

hand and facial injuries.

Sgt.Clarke (FME/AG).

Compressed fracture of the spine.

Sgt Singer ( A/G).

Fractured left arm.

P/O A. Locke.

(W.Op/AG).

Head injury.

Post Processing: light balance, equalization, sharpening

Amtrak P42DC No 5 discharges its cargo at Niagara Falls

Image by JohnGreyTurner

Morse at Hospital

Image by Nickster 2000

Morse enjoying I nice (and expensive) cup of coffee before being discharged at lunchtime.

They said "see you later" as we left!

[taken on the Sony cybershot DSC-200 snappy cam]